Favignana: the Mattanza

The Mattanza was an ancient method of tuna fishing.

As early as mid-April, the Tonnaroti would begin to cast a series of nets into the sea where they would imprison the schools of tuna that, between the second half of May and the first half of June, would leave the ocean to go to the Mediterranean to spawn.

The days of the Mattanza cannot be determined in advance: they depend first and foremost on the path of the tuna and also very much on the sea conditions since the boats used, “le muciare,” are not adapted to cope with swells.

Once upon a time, to witness the Mattanza, one would climb directly into the fishermen’s boats.

The journey of tuna – Following the Atlantic surface current, schools of tuna pass through the Strait of Gibraltar, which officially introduces them into the Mediterranean, and ascend to the northern coasts of Sicily.

At that time, the sea around the Egadi Islands is ideal for spawning: it has a temperature of 17°-18°, a salinity of more than 37 per 1000 and only 20 meters depth.

The Rais – The Mattanza is led by a leader: the Rais. He is the one who decides when to start and when to end the Mattanza, when to open and close the chambers, and he is always the one who gives the orders to the boats, arranging them so that their position facilitates the entry of tuna into the death chamber.

Preparation – The Tonnaroti get into their boats and tie the muciare to each other so that a single motor boat can tow them out to sea.

They interrupt their journey near the St. Peter’s Pole, when the rais also stops to recite the customary prayer. Imitating the rais, the men of the crew uncover their heads.

Then they all set off again to go and arrange themselves according to the pattern created in the sea by buoys and buoy markers.

Chambers – A series of nets forms a sequence of chambers from which tuna, once they enter, cannot leave. The chambers are put in communication with each other through moving nets called “doors.”

Through a system of opening and closing the chambers, the tuna are pushed toward the “death chamber,” which is the only one that also has the net on the bottom: from there the tuna can no longer leave.

The death chamber – When the tuna are in the death chamber, the boats arrange to enclose them inside a square. The men then begin to hoist the door of the chamber. As they pull in the net, the square tightens.

The Rais ‘ “seine” goes to the center of the square where ropes secure it to the north and south sides of the square. From there, he will guide the men to their work. When the voice of the “seiner” rises, all the others join in singing the Cialoma, the ancient songs that set the rhythm for the slaughter.

The men catch the tuna with hooked harpoons and load them onto the boats.

Slowly some tuna die, the water turns red, and, when the Rais deems it most appropriate, his whistle starts the final slaughter.

The re-entry – Slowly the black muciare break the square and line up, almost as in a procession, behind the vessel that first enters the harbor.

The Songs-The Cialome are very ancient folk songs of Arabic origin that set the rhythm of the movements of the tuna fishermen.

Strongly ambiguous and contradictory in nature, on the one hand, they refer to Arabbish motifs and, on the other hand, they invoke, God, Our Lady and Christian saints in order to enjoy a rich catch.

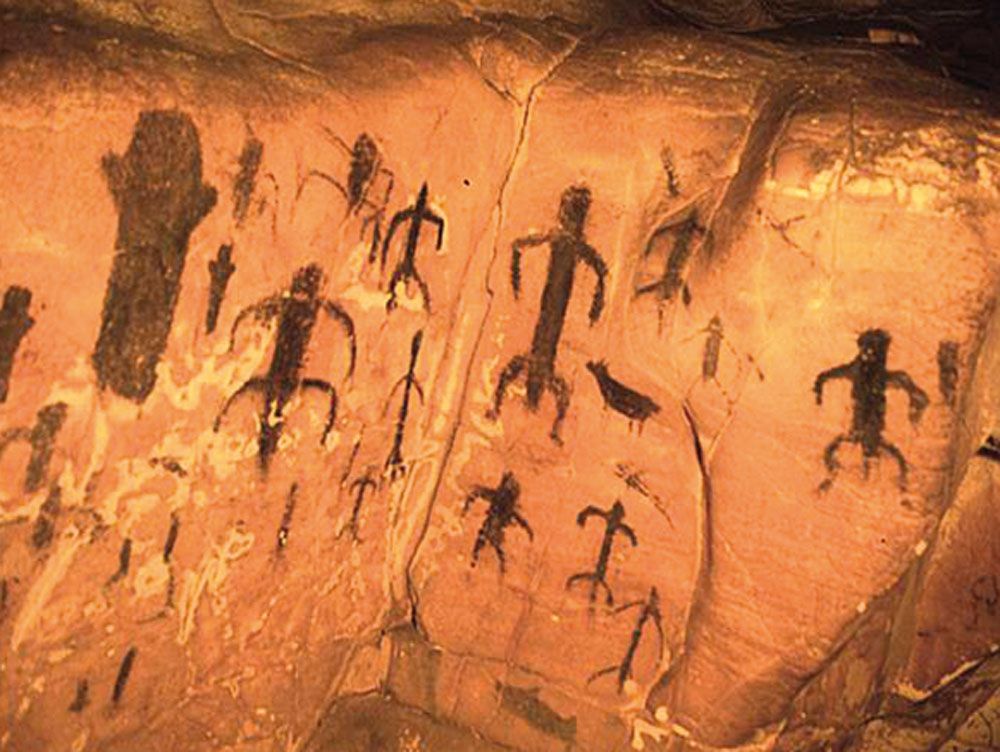

In the past – Tuna fishing in these areas has very remote origins: suffice it to say that in the Genovese Cave(Levanzo-Final Paleolithic phase) two tuna are depicted, and entire tuna vertebrae have been found among the material deposits.

During their stay in the area, the Phoenicians initiated a systematic exploitation of the special climatic conditions that drive tuna shoals here, later imitated by the Romans who built the first, rudimentary warehouses for tuna storage and processing.

The most important trace, however, was left by the Arabs to whom the songs and many of the terms still in use today can be traced.

The Normans incorporated the Tonnare into the state system, according to a highly centralized organization that was maintained for several centuries to come.

In the 17th century, the Tonnara suffered the same fate as many of their estates, which were sold: from 1637 it was owned by the Pallavicini family of Genoa, and then passed into the hands of the Florio and Parodi families.

In 1985 it became the property of the Castiglione company.

For centuries, the Mattanza was the main, if not the only, source of income for the entire island, and as long as it was held, it drew hundreds of spectators to each of its reruns.